In support of Sepideh Jodeyri, the Iranian translator of Blue is the Warmest Color

Julie Maroh began writing and illustrating her story Blue is the Warmest Color when she was 19 years old, and it took her five years to complete. Like anyone with a story to tell, she put a lot of love into her work.

Blue tells the story of Clementine, a high school student who does not identify as a lesbian, who meets Emma, an art student at a nearby university, who, most certainly and confidently, does. It is a coming-of-age story about lesbian love, yes, but also about the elusive quality of love. As with any unforgettable story, any synopsis would be an oversimplification and an understatement. So, suffice it to say that Maroh’s storytelling is tender and her illustrations are vivid.

Only three years after its initial publication, the graphic novel was adapted into an award-winning film of debatable merit. Maroh has described her own response to the film version of her story as just that, a version (for example, Clementine was renamed Adele): "For me this adaptation is another version / vision/ reality of the same story." But it was the lack of lesbians on the film set, and the depiction of lesbian sex filmed by a heterosexual male director and cinematographer that irritated her the most. "What came out of Kechiche’s film reminds me of the little rocks that mutilate our flesh when we fall and scrape ourselves on the asphalt."

I can't really argue with that one! But, back to the comic. Written and originally published in French, Blue has since been translated into 12 languages, the most scandalous of which has been the Persian translation by Sepideh Jodeyri.

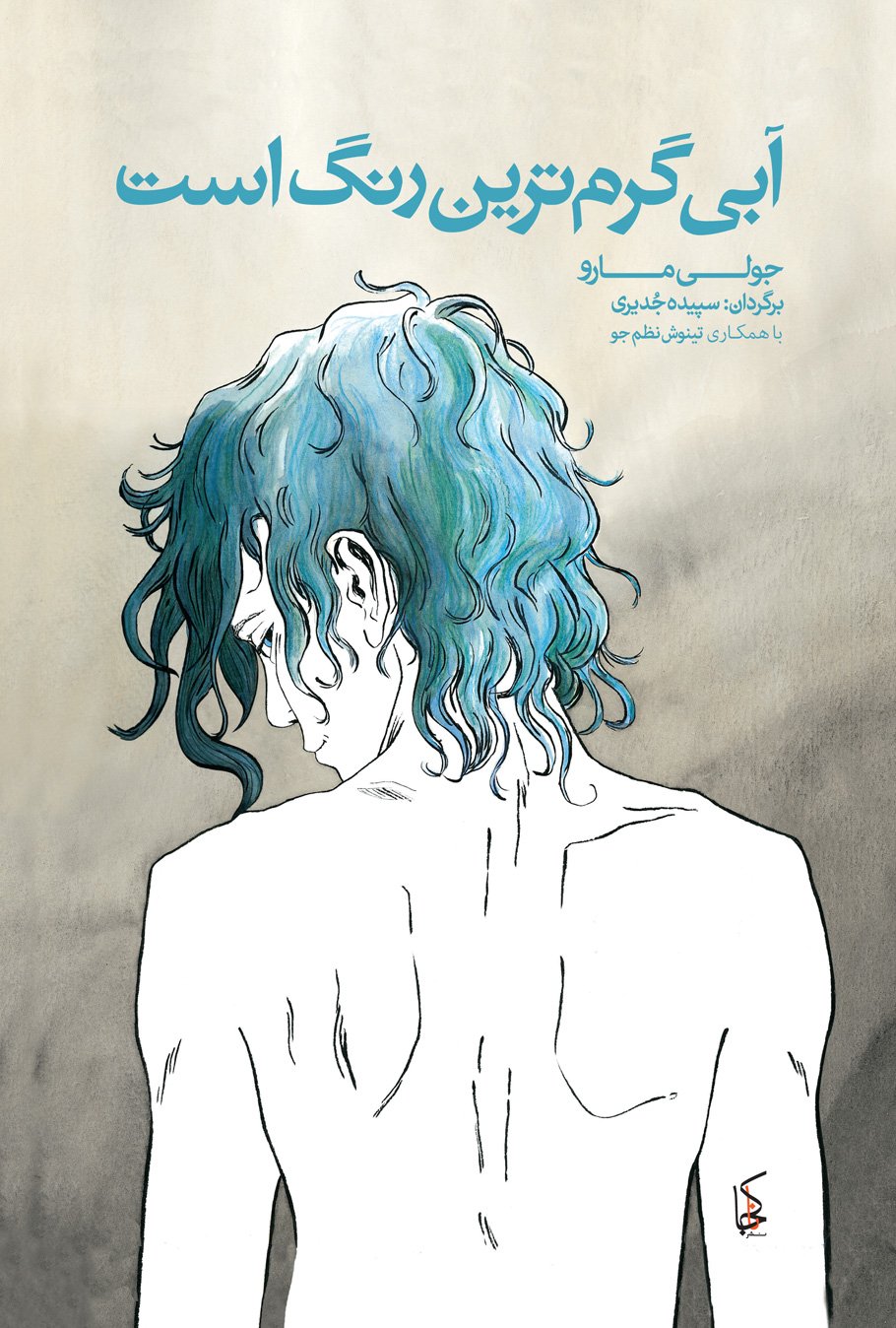

![Cover of the Persian translation of Blue is the Warmest Color.]() Cover of the Persian translation of Blue is the Warmest Color.

Cover of the Persian translation of Blue is the Warmest Color.

Sepideh Jodeyri is a poet, journalist, and literary critic born and raised in Iran. In addition to several books of poetry and a collection of short stories, she has also translated poetry by Edgar Allan Poe (from English) and Jorge Luis Borges (from Spanish). After the controversial 2009 presidential election in Iran, which resulted in the re-election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Jodeyri spoke out publically against his administration and in support of the pro-democracy movement. Soon after that, her work was banned in Iran. She now lives and works in the Czech Republic.

It was by happy chance that Jodeyri discovered Blue. She had heard of the film adaptation, and knew that it had won the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival, but was not aware of the book at the time. When she searched for the DVD on Amazon, she found the English translation of the book before she found the DVD. In her own words: "I say by chance, because I think that the book is so much better than the film."

Her Persian translation was published by Naakojaa, a Persian-language digital publisher based in Paris. It is only available in a digital edition in Iran, although the Kindle edition is available worldwide, and a print edition is available in France.

Although she does not identify as queer, Sepideh Jodeyri is sensitive to LGBT issues: "I am a feminist, which means that I believe in the equality of human rights, for all origins, sexes, religions, sexual orientations." Her dedication is closely connected to her personal memories of Fereydoun Farrokhzzad, the entertainer, activist, and iconic political figure who was forced into exile after Iran's Islamic Revolution in 1979. He was also gay. Jodeyri and her family spent a lot of time with Farrokhzzad, and she tells of him singing and playing the guitar for her when she was a child. Farrokhzzad was killed while living in exile in Germany for what are suspected to be political reasons.

Jodeyri says of Farrokhzzad: "I will never forget the great memories that I have of him and his strong personality." Her support of LGBT rights is, in part, a tribute to him. "I ... fight against dogmatism which exists in ... Iranian society against the LGBT community, via my posts on Facebook, my interviews, my articles, and the translation of (Blue)."

This is especially significant because the rights—and even the existence—of LGBT Iranians have been thoroughly and institutionally denied by the Iranian government. In a speech at Columbia University in New York in 2007, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad famously said: "In Iran we don't have homosexuals like you do in your country … we do not have this phenomenon. I don't know who has told you that we have!"

And of course, nothing could be further from the truth.

In a study conducted by Small Media, a non-profit group based in London, England, researchers gathered first-hand testimonies from hundreds of LGBT Iranians using face-to face-interviews, and when necessary, a secret online forum. One statement in particular—made by Mani, a gay man living in Tehran, who was 24 years old at the time of his interview—says it all: "First, I'd just like to thank Ahmadinejad for saying those things because it finally brought us into the spotlight … How many of us are there? We are innumerable! … We exist! And Mr. Ahmadinejad just needs to open his eyes."

Six years later, though, Mohammad-Javad Larijani, Secretary General of Iran's High Council for Human Rights, said that "promoting homosexuality is illegal and we have strong laws against it," and that "we consider homosexuality an illness that should be cured."

This rationale seems to be that if a human experience does not exist, it is not eligible for basic human rights. Being queer is officially seen as a disease. But it should be obvious that the real illness is hate.

The very acts portrayed in Blue are illegal in Iran. Clementine and Emma would be arrested, subject to corporal punishment, and worse. According to the Islamic Penal Code, the punishment for mosahegheh (lesbianism) is 100 lashes for all individuals involved, and on the fourth offense, death.

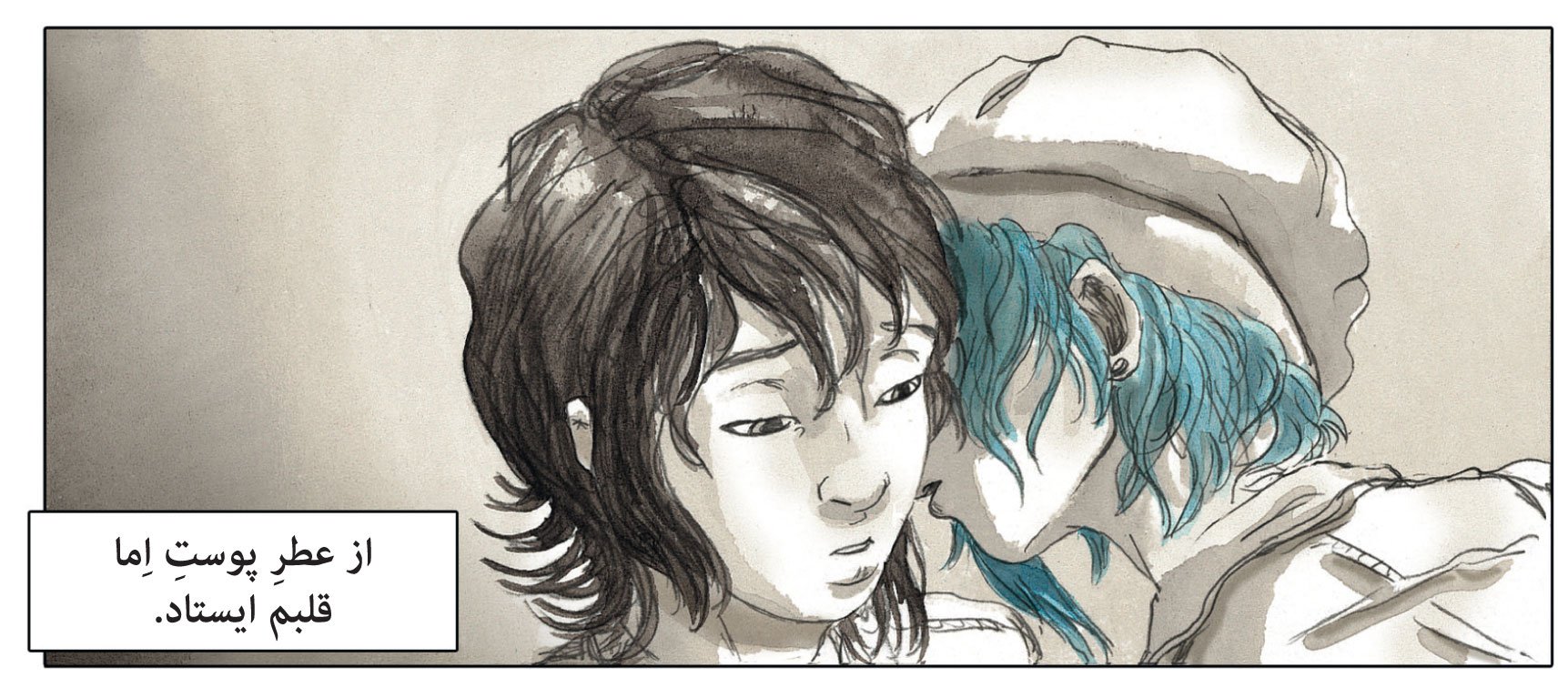

!["The scent of Emma's skin stopped my heart."]() Persian: "The scent of Emma's skin stopped my heart."

Persian: "The scent of Emma's skin stopped my heart."

Although still officially denying anything queer in Iranian culture, the current government, under President Hassan Rouhani, has relaxed some of its restrictions. And although the censorship office at the Ministry of Islamic Guidance continues to vet every book before issuing a publication license, they are less concerned with the personal history of individual authors. Jodeyri was allowed to publish a book of poetry titled And Etc., and it was published without any commotion. However, when the publisher announced a book release party, the conservative media started their witch hunt.

The web-based Raja News (the approximate equivalent of Fox News in Iran) published an article titled "Using Government Resources to Promote a Pro-LGBT Author," calling attention to Jodeyri's Persian translation of Blue. Raja News criticized the new Minister of Culture for allowing Jodeyri's poems to be published, and for allowing the publisher to promote the book in a government-funded building, and recommended that other government agencies intervene and cancel the event. The response was almost immediate: after the article was re-posted on other conservative websites, and published in several daily and weekly papers, the Ministry of Intelligence did intervene, and the event was cancelled. The director of the museum where the party was scheduled to take place was then fired from his job.

In her most recent update, Jodeyri told of an Iranian journalist who did an interview with her about her book, who has had the interview cancelled from publication by the reformist newspaper Shahrvand. The newspaper removed it from their upcoming issue because the articles published by the fundamentalist media against Jodeyri in the recent weeks had made them anxious. In essence, they are afraid that if they publish anything about Sepideh Jodeyri, the authorities will ban their newspaper entirely.

Even two literary critics who have written essays on Jodeyri's book sent her their essays, telling her that anything about her or her works will be censored in the Iranian media, and that it would be better if she sent the essays herself to publications outside of Iran. She closed her update with: "All of this means that my pen is banned in my homeland."

And what ignited this chain reaction was her translation of an LGBT comic. Which reminds us that our stories are important. But also that homophobia is everywhere. Because hate is everywhere.

Indeed, even Arsenal Pulp—the publisher of the English translation of Blue, based in Vancouver—have recently been attacked in the Canadian media for another one of their titles written from the point-of-view of a queer character: When Everything Feels like the Movies by Raziel Reid.

Jodeyri translated Blue to help raise awareness of the LGBT experience in the Persian-speaking world, and to advocate for the rights every person everywhere deserves, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity.

And so, the question is not whether we, queer readers and viewers, read the book or saw the film, or what we thought of either of them. The question is how can we show our solidarity—not only for creators like Julie Maroh, but for allies like Sepideh Joyderi, who help our stories find a wider audience.

This is not about Islam. It's not necessarily about religion at all. And it's not even really about comics. It's about whether love can conquer hate, and what we can do to contribute to that. It's easy to become cynical and even easier to become numb. But the idea that love conquers hate is more than a slogan on a T-shirt.

"It is unbearable to me that such events go uncommented on," says Maroh. "This is one more infringement this year, this life, on our liberty to write, read, communicate, and above all: love. We're going to need much—M-U-C-H—love this year."

Sepideh came to Julie to have her story told, and in turn, Julie asks that we spread the word, in the hope that it will bring these results (translated* from her blog):

1: For the censorship, pressure, and imprisonment of LGBT people in Iran to stop

2: For LGBT people in Iran and elsewhere to not feel isolated

3: And if anyone, anywhere, is tempted to follow Iran's example, may they be warned that we are able to mobilize ourselves against such hate.

Please spread the word about Sepideh Joyderi—on Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, anywhere. She is an ally and a warrior. Help raise awareness of state-sanctioned hate in our world. Spread some love. Help love conquer hate.

!["Unicorn Pride No Censure" by Julie Maroh]()

"Unicorn Pride No Censure" by Julie Maroh

*Although Julie Maroh's blog includes an English translation, the translation in this article is my own translation of her original French.